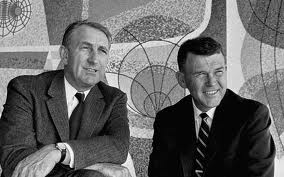

David Packard, who founded the American electronics giant Hewlett-Packard in the nineteen-thirties with his Stanford University pal Bill Hewlett, working out of a garage in Palo Alto California, reminds me of James Stewart. You may have found yourself slumped in front of a TV at Christmas watching James Stewart in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. If you are a Hitchcock fan, you may know Stewart from Rear Window or Vertigo. To confuse the picture considerably, if you like the musical High Society, starring Grace Kelly, Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra, you may have enjoyed the earlier non-musical version of the film, The Philadelphia Story, which is far truer to the original stage version of the play, and in which film James ‘Jimmy’ Stewart stars alongside Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn.

The point is that if you have ever seen James Stewart in a film, you will instantly recognise that he is the embodiment of the kind of deep-down decent, self-effacing, hard-working, independent, old-fashioned, do-the-right-thing values that made America great. Jimmy (‘aw, shucks’) Stewart could not tell a lie. If, as George Washington never did, he had as a boy cut down a treasured cherry tree in his father’s orchard, he would have rushed up to dad and said, ‘Father, I cannot tell a lie. I cut down that tree with my little hatchet.’ As you do.

Stewart was a war hero – of course. Both of his grandfathers fought in the American Civil War. His father fought in WW1. James flew B-24 Liberators on bombing raids over Germany in 1944. Having been promoted from Captain to Major, James chose to inspire his rather shaky team of young, inexperienced American flyers by personally piloting the lead B-24 on bombing sorties deep into German territory – something that his rank did not oblige him to do, and an extremely life-threatening activity to undertake voluntarily. Stewart also insisted that these sorties were not recorded on his tally of combat flights (which is taking decency to extremes). He was twice awarded America’s Distinguished Flying Cross for bravery in action. The French awarded Stewart the Croix de Guerre for his role in the liberation of Europe. He was eventually promoted to the rank of Colonel, making Stewart one of the few Americans to rise from the rank of Private to Colonel during the course of the war.

You get my point. Jimmy Stewart: the kind of guy who made America great but doesn’t want to make a big fuss about it. Slightly earnest; successful but self-deprecating; neighbourly; loyal; patriotic; living ordinary life in an heroic mode; decent.

David Packard was a bit like that.

“Companies exist to make a contribution . . .” The HP Objectives

What I like about Packard is that he espouses the kind of corporate values that many of us would like to believe in – except that we are constantly told by people who prefer the redder-in-tooth-and-claw brand of capitalism that this is all very charming (and soggy and liberal) but, more to the point, it will never work.

‘I want to discuss why a company exists in the first place,’ said Packard. ‘In other words, why are we here? I think many people assume, wrongly, that a company exists simply to make money. While this is an important result of a company’s existence, we have to go deeper and find the real reasons for our being. As we investigate this, we inevitably come to the conclusion that a group of people get together and exist as an institution that we call a company so that they are able to accomplish something collectively which they could not accomplish separately. They are able to do something worthwhile – they make a contribution to society (a phrase which sounds trite but is fundamental). [. . .] You can look around and still see people who are interested in money and nothing else, but the underlying drives come largely from a desire to do something else – to make a product – to give a service – generally to do something that is of value.’

You have to remind yourself that this apparently unworldly hippy started out making electronic measuring instruments in a garage with his college friend, Bill, in 1939 and created a company that recorded annual revenues of $31.5 billion and profits of $2.4 billion in 1996 (the year of David Packard’s death) and was, at that time, ranked 20th in the Fortune 500. But then David and Bill were never flaky about the need to make profit. ‘Profit’, says David, ‘is the best single measure of our contribution to society and the ultimate source of our corporate strength. We should attempt to achieve the maximum possible profit consistent with our other objectives’.

And those other objectives? Constantly improving customer satisfaction and a continual improvement in the quality, usefulness and value of the products that HP manufactures; constant growth – but only in those areas that HP has identified as being ‘fields in which we have capability and can make a contribution’.

After these objectives come the unusual HP objectives, or values. They are not, actually, ‘unusual’, in the sense that many companies express their belief in these kinds of values all of the time. It’s just that most companies don’t seem to genuinely believe in these principles and, if they do, they don’t actually implement these principles:

‘To provide employment opportunities for HP people that include the opportunity to share in the company’s success, which they help make possible. To provide for them job security based on performance, and to provide the opportunity for personal satisfaction that comes from a sense of accomplishment in their work.

‘To maintain an organisational environment that fosters individual motivation, initiative and creativity, and a wide latitude of freedom in working towards established objectives and goals.

‘To meet the obligations of good citizenship by making contributions to the community and to the institutions in our society which generate the environment in which we operate.’

Hewlett and Packard also embraced another principle to which other companies give only lip service at best: ‘. . . our success depends in large part on giving the responsibility to the level where it can be exercised effectively, usually on the lowest possible level of the organisation, the level nearest to the customer.’

And, finally, ‘. . . people work to make contribution and they do this best when they have a real objective when they know what they are trying to achieve and are able to use their own capabilities to the greatest extent. This is a basic philosophy . . . Management by Objective as compared to Management by Control.’

“Contempt and defiance beyond the normal call of engineering duty”

My favourite David Packard story illustrates many of these principles in action. Not in some kind of rose-tinted corporate memory, but in a genuine, real-life, job-threatening scenario.

Hewlett Packard knew that the continuous development of new products was essential not only to their growth but to their survival. Along the way many promising new products had to be abandoned. Packard recognises that telling a team that their pet project would not see the light of day – while ensuring that they remained motivated to devise and develop the next generation of new products – was one of the hardest of management tasks.

A Hewlett Packard engineer, Chuck House, had been developing a display monitor. He knew that customers wanted the product, and that it had the right features. David Packard didn’t believe that the product had a profitable future and says that he ‘among others, had requested it to be discontinued.’

I like that word ‘requested’. In most companies, when the CEO and owner of the company ‘requests’ that something should happen, there isn’t much subsequent debate.

But Chuck was not to be stopped. ‘He persuaded his R&D manager’ – and I am quoting here from Packard’s book, The HP Way – ‘to rush the monitor into production.’ And gee whiz, says Packard in retrospect, we sold more than seventeen thousand of those display monitors, making the company over $35 million in sales.

Some years later, Packard presented Chuck with a medal for ‘extraordinary contempt and defiance beyond the normal call of engineering duty’. And this wasn’t merely a face-saving process for Packard (as in: ‘Give the guy a phoney medal and then send him to Siberia.’) Packard forgave Chuck because of the intent of his defiance. ‘I wasn’t trying to be defiant or obstreperous,’ said Chuck, ‘I really just wanted a success for HP. It never occurred to me that it might cost me my job’. Chuck House was later promoted to be director of a department, ‘with his reputation as a maverick intact’.

Real devolution in practice. The result? Real innovation.

For me, the impressive thing about this story is that Chuck was able to ‘persuade’ his R&D manager to rush the monitor into production. This proves one of two things: either Packard was absolutely genuine about his principle of devolving decision-making down the management chain to be as close as possible to consumers and to the real world (in which case he genuinely was not aware of the decision until the monitor was in production – which is impressive in terms of relinquishing managerial control), or he was indeed made aware of the decision at some routine meeting, but decided to let it go. Either way, that is real devolution in practice: the boss decides he doesn’t want something to happen, but somebody a long way down the hierarchy makes it happen anyway. And Packard rides with that and publically rewards the culprit for his insubordination because it resulted in success. I don’t think that we have to agonise about what would have happened to Chuck if his monitors had bombed.

The impact that Packard’s charismatic personality and his thoughtfully expressed corporate philosophy had on his employees lasted for decades. The long shadow cast by Packard and Hewlett was such that, six decades later, in the nineteen-nineties, the company was still debating whether Dave and Bill would have been happy about a certain change to the company or a possible new direction. It is impressive in terms of the deeply-engrained cultural legacy that the founders had managed to establish, but it is also almost certainly a dangerous burden for a company facing the inevitable upheavals that changing markets force on every organisation.

Ironically, Bill and David understood the need for constant change perfectly. “To remain static is to lose ground,” said Packard. He and Bill changed the management structure of the company significantly on two separate occasion in order to cope with the challenges imposed by their rapidly increasing size, while still retaining the corproate values that they believed in. In the early nineteen nineties, the two founders realised that the new computer business needed a greater degree of coordination than their previous, instrument-based business. Computers need many different elements – equipment, operating systems, software, peripherals – to be brought together to deliver working systems. Councils and committees were created to coordinate the new division’s efforts. And then Hewlett and Packard realised that a cumbersome bureaucracy had been created. “Eventually,” (after the founders had visited many HP locations and talked with hundreds of employees), “we knew what we needed to do. Too many layers of management had been built into the organisation. We reduced them . . . Most important, computer operating units were given greater freedom to create their own plans and make their own decisions, resulting in a much more flexible and agile company.”

It’s that devolution thing again.

Packard continues: “In 1993, our stock was up to $70. As of writing,” (1995, the year before David Packard’s death), “it’s over $100 and about to be split.”

Oh, those hopeless hippies, with their wacky notion of devolving power to the workers. It will never make money.

It does make you think.

And here’s another classic, apparent HP conundrum. An HP marketing manager, Bill Krause, was laid up for eight months in 1970 after a car crash. David Packard called Krause in hospital to assure him that his job was safe. Eight years later, Krause was making a presentation about consumer satisfaction with HP computer products. The results aren’t good. Packard interrupts the presentation. “Customer satisfaction second to none is the only acceptable goal. If you cannot lead your organisation to achieve that goal, I’m sure we can find someone who can.”

So the man who can go out of his way to ensure that an employee that prolonged but unavoidable sick-leave will not jeopardise his career, can also tell the same man, some years later, to shape up or ship out.

It works for me.

But, when the founders have left the picture, how does new management cope with change to an organisation that has ‘The HP Way’ written right though it like a stick of rock? John Young and then Lew Platt took up the torch, but made no radical changes to the company’s structure. Then, in 1998, the board of directors selected a charismatic young female as the new CEO: Carly Fiorina, whom Fortune magazine had just named as ‘the most powerful woman in business’ because of her role at Lucent Technologies. To read more about how Fiorina changed the organisation – and what can be learned from how she went about it – see Changing a Heritage Culture: HP and Carly Fiorina.

Source: David Packard, The HP Way, Harper Collins, New York, 1995